User:Amimouni

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user whom this page is about may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Amimouni. |

Pablo Picasso | |

|---|---|

Picasso in 1908 | |

| Born | Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso[1] 25 October 1881 Málaga, Spain |

| Died | 8 April 1973 (aged 91) Mougins, France |

| Resting place | Château of Vauvenargues 43°33′15″N 5°36′16″E / 43.554142°N 5.604438°E |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Education | José Ruiz y Blasco (father), Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, sculpture printmaking, ceramics, stage design, writing |

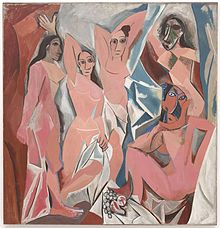

| Notable work | Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) Guernica (1937) The Weeping Woman (1937) |

| Movement | Cubism, Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) | Olga Khokhlova (1918–55) Jacqueline Roque (1961–73) |

Pablo Ruiz y Picasso, also known as Pablo Picasso (/pɪˈkɑːsoʊ, -ˈkæsoʊ/;[2] Spanish: [ˈpaβlo piˈkaso]; 25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973), was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet and playwright who spent most of his adult life in France. As one of the greatest and most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture,[3][4] the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), and Guernica (1937), a portrayal of the Bombing of Guernica by the German and Italian airforces at the behest of the Spanish nationalist government during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso, Henri Matisse and Marcel Duchamp are regarded as the three artists who most defined the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the 20th century, responsible for significant developments in painting, sculpture, printmaking and ceramics.[5][6][7][8]

Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence. During the first decade of the 20th century, his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques, and ideas. His work is often categorized into periods. While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901–1904), the Rose Period (1904–1906), the African-influenced Period (1907–1909), Analytic Cubism (1909–1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal period.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments, and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

Early life[edit]

Picasso was baptized Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso,[1] a series of names honoring various saints and relatives.[9] Ruiz y Picasso were included for his father and mother, respectively, as per Spanish law. Born in the city of Málaga in the Andalusian region of Spain, he was the first child of Don José Ruiz y Blasco (1838–1913) and María Picasso y López.[10] Though baptized a Catholic, Picasso would later on become an atheist.[11] Picasso's family was of middle-class background. His father was a painter who specialized in naturalistic depictions of birds and other game. For most of his life Ruiz was a professor of art at the School of Crafts and a curator of a local museum. Ruiz's ancestors were minor aristocrats.

Picasso showed a passion and a skill for drawing from an early age. According to his mother, his first words were "piz, piz", a shortening of lápiz, the Spanish word for "pencil".[12] From the age of seven, Picasso received formal artistic training from his father in figure drawing and oil painting. Ruiz was a traditional academic artist and instructor, who believed that proper training required disciplined copying of the masters, and drawing the human body from plaster casts and live models. His son became preoccupied with art to the detriment of his classwork.

%2C_oil_on_cardboard%2C_67_x_52.1_cm%2C_Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art.jpg/220px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1901%2C_Old_Woman_(Woman_with_Gloves)%2C_oil_on_cardboard%2C_67_x_52.1_cm%2C_Philadelphia_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_73_x_54_cm%2C_Hermitage_Museum%2C_Saint_Petersburg%2C_Russia.jpg/220px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1901-02%2C_Femme_au_café_(Absinthe_Drinker)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_73_x_54_cm%2C_Hermitage_Museum%2C_Saint_Petersburg%2C_Russia.jpg)

The family moved to A Coruña in 1891, where his father became a professor at the School of Fine Arts. They stayed almost four years. On one occasion, the father found his son painting over his unfinished sketch of a pigeon. Observing the precision of his son's technique, an apocryphal story relates, Ruiz felt that the thirteen-year-old Picasso had surpassed him, and vowed to give up painting,[13] though paintings by him exist from later years.

In 1895, Picasso was traumatized when his seven-year-old sister, Conchita, died of diphtheria.[14] After her death, the family moved to Barcelona, where Ruiz took a position at its School of Fine Arts. Picasso thrived in the city, regarding it in times of sadness or nostalgia as his true home.[15] Ruiz persuaded the officials at the academy to allow his son to take an entrance exam for the advanced class. This process often took students a month, but Picasso completed it in a week, and the jury admitted him, at just 13. The student lacked discipline but made friendships that would affect him in later life. His father rented a small room for him close to home so he could work alone, yet he checked up on him numerous times a day, judging his drawings. The two argued frequently.

Picasso's father and uncle decided to send the young artist to Madrid's Royal Academy of San Fernando, the country's foremost art school.[15] At age 16, Picasso set off for the first time on his own, but he disliked formal instruction and stopped attending classes soon after enrollment. Madrid held many other attractions. The Prado housed paintings by Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya, and Francisco Zurbarán. Picasso especially admired the works of El Greco; elements such as his elongated limbs, arresting colors, and mystical visages are echoed in Picasso's later work.

Career beginnings[edit]

Before 1900[edit]

Picasso's training under his father began before 1890. His progress can be traced in the collection of early works now held by the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, which provides one of the most comprehensive records extant of any major artist's beginnings.[16] During 1893 the juvenile quality of his earliest work falls away, and by 1894 his career as a painter can be said to have begun.[17] The academic realism apparent in the works of the mid-1890s is well displayed in The First Communion (1896), a large composition that depicts his sister, Lola. In the same year, at the age of 14, he painted Portrait of Aunt Pepa, a vigorous and dramatic portrait that Juan-Eduardo Cirlot has called "without a doubt one of the greatest in the whole history of Spanish painting."[18]

In 1897 his realism became tinged with Symbolist influence, in a series of landscape paintings rendered in non-naturalistic violet and green tones. What some call his Modernist period (1899–1900) followed. His exposure to the work of Rossetti, Steinlen, Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch, combined with his admiration for favorite old masters such as El Greco, led Picasso to a personal version of modernism in his works of this period.[19]

Picasso made his first trip to Paris, then the art capital of Europe, in 1900. There, he met his first Parisian friend, journalist and poet Max Jacob, who helped Picasso learn the language and its literature. Soon they shared an apartment; Max slept at night while Picasso slept during the day and worked at night. These were times of severe poverty, cold, and desperation. Much of his work was burned to keep the small room warm. During the first five months of 1901, Picasso lived in Madrid, where he and his anarchist friend Francisco de Asís Soler founded the magazine Arte Joven (Young Art), which published five issues. Soler solicited articles and Picasso illustrated the journal, mostly contributing grim cartoons depicting and sympathizing with the state of the poor. The first issue was published on 31 March 1901, by which time the artist had started to sign his work Picasso; before he had signed Pablo Ruiz y Picasso.[20]

Blue Period[edit]

Picasso's Blue Period (1901–1904), characterized by somber paintings rendered in shades of blue and blue-green, only occasionally warmed by other colors, began either in Spain in early 1901, or in Paris in the second half of the year.[21] Many paintings of gaunt mothers with children date from the Blue Period, during which Picasso divided his time between Barcelona and Paris. In his austere use of color and sometimes doleful subject matter – prostitutes and beggars are frequent subjects – Picasso was influenced by a trip through Spain and by the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas. Starting in autumn of 1901 he painted several posthumous portraits of Casagemas, culminating in the gloomy allegorical painting La Vie (1903), now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.[22]

Infrared imagery of Picasso's 1901 painting The Blue Room reveals another painting beneath the surface.[23]

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_99.1_x_100.3_cm%2C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg/220px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1905%2C_Au_Lapin_Agile_(At_the_Lapin_Agile)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_99.1_x_100.3_cm%2C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

The same mood pervades the well-known etching The Frugal Repast (1904),[24] which depicts a blind man and a sighted woman, both emaciated, seated at a nearly bare table. Blindness is a recurrent theme in Picasso's works of this period, also represented in The Blindman's Meal (1903, the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and in the portrait of Celestina (1903). Other works include Portrait of Soler and Portrait of Suzanne Bloch.

Rose Period[edit]

The Rose Period (1904–1906)[25] is characterized by a more cheery style with orange and pink colors, and featuring many circus people, acrobats and harlequins known in France as saltimbanques. The harlequin, a comedic character usually depicted in checkered patterned clothing, became a personal symbol for Picasso. Picasso met Fernande Olivier, a bohemian artist who became his mistress, in Paris in 1904.[14] Olivier appears in many of his Rose Period paintings, many of which are influenced by his warm relationship with her, in addition to his increased exposure to French painting. The generally upbeat and optimistic mood of paintings in this period is reminiscent of the 1899–1901 period (i.e. just prior to the Blue Period) and 1904 can be considered a transition year between the two periods.

By 1905, Picasso became a favorite of American art collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein. Their older brother Michael Stein and his wife Sarah also became collectors of his work. Picasso painted portraits of both Gertrude Stein and her nephew Allan Stein. Gertrude Stein became Picasso's principal patron, acquiring his drawings and paintings and exhibiting them in her informal Salon at her home in Paris.[27] At one of her gatherings in 1905, he met Henri Matisse, who was to become a lifelong friend and rival. The Steins introduced him to Claribel Cone and her sister Etta who were American art collectors; they also began to acquire Picasso and Matisse's paintings. Eventually Leo Stein moved to Italy. Michael and Sarah Stein became patrons of Matisse, while Gertrude Stein continued to collect Picasso.[28]

In 1907 Picasso joined an art gallery that had recently been opened in Paris by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Kahnweiler was a German art historian and art collector who became one of the premier French art dealers of the 20th century. He was among the first champions of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and the Cubism that they jointly developed. Kahnweiler promoted burgeoning artists such as André Derain, Kees van Dongen, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Maurice de Vlaminck and several others who had come from all over the globe to live and work in Montparnasse at the time.[29]

Modern art transformed[edit]

African-influenced Period[edit]

Picasso's African-influenced Period (1907–1909) begins with the two figures on the right in his painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which were inspired by African artefacts. Formal ideas developed during this period lead directly into the Cubist period that follows.

Cubism[edit]

Analytic cubism (1909–1912) is a style of painting Picasso developed with Georges Braque using monochrome brownish and neutral colors. Both artists took apart objects and "analyzed" them in terms of their shapes. Picasso and Braque's paintings at this time share many similarities. Synthetic cubism (1912–1919) was a further development of the genre, in which cut paper fragments – often wallpaper or portions of newspaper pages – were pasted into compositions, marking the first use of collage in fine art.

In Paris, Picasso entertained a distinguished coterie of friends in the Montmartre and Montparnasse quarters, including André Breton, poet Guillaume Apollinaire, writer Alfred Jarry, and Gertrude Stein. Apollinaire was arrested on suspicion of stealing the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. Apollinaire pointed to his friend Picasso, who was also brought in for questioning, but both were later exonerated.[30]

Crystal period[edit]

Between 1915 and 1917, Picasso began a series of paintings depicting highly geometric and minimalist Cubist objects, consisting of either a pipe, a guitar or a glass, with an occasional element of collage. "Hard-edged square-cut diamonds", notes art historian John Richardson, "these gems do not always have upside or downside".[31][32] "We need a new name to designate them," wrote Picasso to Gertrude Stein: Maurice Raynal suggested "Crystal Cubism".[31][33] These "little gems" may have been produced by Picasso in response to critics who had claimed his defection from the movement, through his experimentation with classicism within the so-called return to order following the war.[31][34]

-

1909, Femme assise (Sitzende Frau), oil on canvas, 100 × 80 cm, Staatliche Museen, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

-

1909–10, Figure dans un Fauteuil (Seated Nude, Femme nue assise), oil on canvas, 92.1 × 73 cm, Tate Modern, London. This painting from the collection of Wilhelm Uhde was confiscated by the French state and sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921

-

1910, Woman with Mustard Pot (La Femme au pot de moutarde), oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague. Exhibited at the Armory Show, New York, Chicago, Boston 1913

-

1910, Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier), oil on canvas, 100.3 × 73.6 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

1910, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, The Art Institute of Chicago. Picasso wrote of Kahnweiler "What would have become of us if Kahnweiler hadn't had a business sense?"

-

1910–11, Guitariste, La mandoliniste (Woman playing guitar or mandolin), oil on canvas

-

1911, Still Life with a Bottle of Rum, oil on canvas, 61.3 × 50.5 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

1911, The Poet (Le poète), oil on linen, 131.2 × 89.5 cm (51 5/8 × 35 1/4 in), The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

-

1911–12, Violon (Violin), oil on canvas, 100 × 73 cm (oval), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands. This painting from the collection of Wilhelm Uhde was confiscated by the French state and sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921

-

1913, Bouteille, clarinet, violon, journal, verre, 55 × 45 cm. This painting from the collection of Wilhelm Uhde was confiscated by the French state and sold at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921

-

1913, Femme assise dans un fauteuil (Eva), Woman in a Chemise in an Armchair, oil on canvas, 149.9 × 99.4 cm, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

1913–14, Head (Tête), cut and pasted colored paper, gouache and charcoal on paperboard, 43.5 × 33 cm, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

-

1913–14, L'Homme aux cartes (Card Player), oil on canvas, 108 × 89.5 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

1914–15, Nature morte au compotier (Still Life with Compote and Glass), oil on canvas, 63.5 × 78.7 cm (25 × 31 in), Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

-

1916, L'anis del mono (Bottle of Anis del Mono), oil on canvas, 46 × 54.6 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan

Fame[edit]

After acquiring some fame and fortune, Picasso left Olivier for Marcelle Humbert, who he called Eva Gouel. Picasso included declarations of his love for Eva in many Cubist works. Picasso was devastated by her premature death from illness at the age of 30 in 1915.[35]

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_130_x_88.8_cm%2C_Musée_Picasso%2C_Paris%2C_France.jpg/170px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1917-18%2C_Portrait_d%27Olga_dans_un_fauteuil_(Olga_in_an_Armchair)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_130_x_88.8_cm%2C_Musée_Picasso%2C_Paris%2C_France.jpg)

At the outbreak of World War I (August 1914) Picasso lived in Avignon. Braque and Derain were mobilized and Apollinaire joined the French artillery, while the Spaniard Juan Gris remained from the Cubist circle. During the war Picasso was able to continue painting uninterrupted, unlike his French comrades. His paintings became more sombre and his life changed with dramatic consequences. Kahnweiler’s contract had terminated on his exile from France. At this point Picasso’s work would be taken on by the art dealer Léonce Rosenberg. After the loss of Eva Gouel, Picasso had an affair with Gaby Lespinasse. During the spring of 1916 Apollinaire returned from the front wounded. They renewed their friendship, but Picasso began to frequent new social circles.[36]

Towards the end of World War I, Picasso made a number of important relationships with figures associated with Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Among his friends during this period were Jean Cocteau, Jean Hugo, Juan Gris, and others. In the summer of 1918, Picasso married Olga Khokhlova, a ballerina with Sergei Diaghilev's troupe, for whom Picasso was designing a ballet, Erik Satie's Parade, in Rome; they spent their honeymoon near Biarritz in the villa of glamorous Chilean art patron Eugenia Errázuriz.

After return from honeymoon, and in desperate need of money, Picasso started his exclusive relationship with the French-Jewish art dealer Paul Rosenberg. As part of his first duties, Rosenberg agreed to rent the couple an apartment in Paris at his own expense, which was located next to his own house. This was the start of a deep brother-like friendship between two very different men, that would last until the outbreak of World War II.

Khokhlova introduced Picasso to high society, formal dinner parties, and all the social niceties attendant to the life of the rich in 1920s Paris. The two had a son, Paulo,[37] who would grow up to be a dissolute motorcycle racer and chauffeur to his father. Khokhlova's insistence on social propriety clashed with Picasso's bohemian tendencies and the two lived in a state of constant conflict. During the same period that Picasso collaborated with Diaghilev's troupe, he and Igor Stravinsky collaborated on Pulcinella in 1920. Picasso took the opportunity to make several drawings of the composer.

In 1927 Picasso met 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter and began a secret affair with her. Picasso's marriage to Khokhlova soon ended in separation rather than divorce, as French law required an even division of property in the case of divorce, and Picasso did not want Khokhlova to have half his wealth. The two remained legally married until Khokhlova's death in 1955. Picasso carried on a long-standing affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter and fathered a daughter with her, named Maya. Marie-Thérèse lived in the vain hope that Picasso would one day marry her, and hanged herself four years after Picasso's death. Throughout his life Picasso maintained several mistresses in addition to his wife or primary partner. Picasso was married twice and had four children by three women:

- Paulo (4 February 1921 – 5 June 1975) (Born Paul Joseph Picasso) – with Olga Khokhlova

- Maya (5 September 1935 – ) (Born Maria de la Concepcion Picasso) – with Marie-Thérèse Walter

- Claude (15 May 1947 –) (Born Claude Pierre Pablo Picasso) – with Françoise Gilot

- Paloma (19 April 1949 – ) (Born Anne Paloma Picasso) – with Françoise Gilot

Photographer and painter Dora Maar was also a constant companion and lover of Picasso. The two were closest in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and it was Maar who documented the painting of Guernica.

Classicism and surrealism[edit]

In February 1917, Picasso made his first trip to Italy.[38] In the period following the upheaval of World War I, Picasso produced work in a neoclassical style. This "return to order" is evident in the work of many European artists in the 1920s, including André Derain, Giorgio de Chirico, Gino Severini, Jean Metzinger, the artists of the New Objectivity movement and of the Novecento Italiano movement. Picasso's paintings and drawings from this period frequently recall the work of Raphael and Ingres.

In 1925 the Surrealist writer and poet André Breton declared Picasso as 'one of ours' in his article Le Surréalisme et la peinture, published in Révolution surréaliste. Les Demoiselles was reproduced for the first time in Europe in the same issue. Yet Picasso exhibited Cubist works at the first Surrealist group exhibition in 1925; the concept of 'psychic automatism in its pure state' defined in the Manifeste du surréalisme never appealed to him entirely. He did at the time develop new imagery and formal syntax for expressing himself emotionally, "releasing the violence, the psychic fears and the eroticism that had been largely contained or sublimated since 1909", writes art historian Melissa McQuillan.[39] Although this transition in Picasso's work was informed by Cubism for its spatial relations, "the fusion of ritual and abandon in the imagery recalls the primitivism of the Demoiselles and the elusive psychological resonances of his Symbolist work", writes McQuillan.[39] Surrealism revived Picasso’s attraction to primitivism and eroticism.[39]

During the 1930s, the minotaur replaced the harlequin as a common motif in his work. His use of the minotaur came partly from his contact with the surrealists, who often used it as their symbol, and it appears in Picasso's Guernica. The minotaur and Picasso's mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter are heavily featured in his celebrated Vollard Suite of etchings.[40]

In 1939–40 the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, under its director Alfred Barr, a Picasso enthusiast, held a major retrospective of Picasso's principal works until that time. This exhibition lionized the artist, brought into full public view in America the scope of his artistry, and resulted in a reinterpretation of his work by contemporary art historians and scholars.[41]

Arguably Picasso's most famous work is his depiction of the German bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War – Guernica. This large canvas embodies for many the inhumanity, brutality and hopelessness of war. Asked to explain its symbolism, Picasso said, "It isn't up to the painter to define the symbols. Otherwise it would be better if he wrote them out in so many words! The public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them."[42][43]

Guernica was on display in New York's Museum of Modern Art for many years. In 1981, it was returned to Spain and was on exhibit at the Casón del Buen Retiro. In 1992 the painting was put on display in Madrid's Reina Sofía Museum when it opened.

World War II and beyond[edit]

During the Second World War, Picasso remained in Paris while the Germans occupied the city. Picasso's artistic style did not fit the Nazi ideal of art, so he did not exhibit during this time. He was often harassed by the Gestapo. During one search of his apartment, an officer saw a photograph of the painting Guernica. "Did you do that?" the German asked Picasso. "No," he replied, "You did".[44]

Retreating to his studio, he continued to paint, producing works such as the Still Life with Guitar (1942) and The Charnel House (1944–48).[45] Although the Germans outlawed bronze casting in Paris, Picasso continued regardless, using bronze smuggled to him by the French Resistance.[46]

Around this time, Picasso took up writing as an alternative outlet. Between 1935 and 1959 he wrote over 300 poems. Largely untitled except for a date and sometimes the location of where it was written (for example "Paris 16 May 1936"), these works were gustatory, erotic and at times scatological, as were his two full-length plays Desire Caught by the Tail (1941) and The Four Little Girls (1949).[48][49]

In 1944, after the liberation of Paris, Picasso, then 63 years old, began a romantic relationship with a young art student named Françoise Gilot. She was 40 years younger than he was. Picasso grew tired of his mistress Dora Maar; Picasso and Gilot began to live together. Eventually they had two children: Claude, born in 1947 and Paloma, born in 1949. In her 1964 book Life with Picasso,[50] Gilot describes his abusive treatment and myriad infidelities which led her to leave him, taking the children with her. This was a severe blow to Picasso.

Picasso had affairs with women of an even greater age disparity than his and Gilot's. While still involved with Gilot, in 1951 Picasso had a six-week affair with Geneviève Laporte, who was four years younger than Gilot. By his 70s, many paintings, ink drawings and prints have as their theme an old, grotesque dwarf as the doting lover of a beautiful young model. Jacqueline Roque (1927–1986) worked at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris on the French Riviera, where Picasso made and painted ceramics. She became his lover, and then his second wife in 1961. The two were together for the remainder of Picasso's life.

His marriage to Roque was also a means of revenge against Gilot; with Picasso's encouragement, Gilot had divorced her then husband, Luc Simon, with the plan to marry Picasso to secure the rights of her children as Picasso's legitimate heirs. Picasso had already secretly married Roque, after Gilot had filed for divorce. This strained his relationship with Claude and Paloma.

By this time, Picasso had constructed a huge Gothic home, and could afford large villas in the south of France, such as Mas Notre-Dame-de-Vie on the outskirts of Mougins, and in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur. He was an international celebrity, with often as much interest in his personal life as his art.

In addition to his artistic accomplishments, Picasso made a few film appearances, always as himself, including a cameo in Jean Cocteau's Testament of Orpheus. In 1955 he helped make the film Le Mystère Picasso (The Mystery of Picasso) directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot.

Later works[edit]

Picasso was one of 250 sculptors who exhibited in the 3rd Sculpture International held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in mid-1949. In the 1950s, Picasso's style changed once again, as he took to producing reinterpretations of the art of the great masters. He made a series of works based on Velázquez's painting of Las Meninas. He also based paintings on works by Goya, Poussin, Manet, Courbet and Delacroix.

He was commissioned to make a maquette for a huge 50-foot (15 m)-high public sculpture to be built in Chicago, known usually as the Chicago Picasso. He approached the project with a great deal of enthusiasm, designing a sculpture which was ambiguous and somewhat controversial. What the figure represents is not known; it could be a bird, a horse, a woman or a totally abstract shape. The sculpture, one of the most recognizable landmarks in downtown Chicago, was unveiled in 1967. Picasso refused to be paid $100,000 for it, donating it to the people of the city.

Picasso's final works were a mixture of styles, his means of expression in constant flux until the end of his life. Devoting his full energies to his work, Picasso became more daring, his works more colorful and expressive, and from 1968 to 1971 he produced a torrent of paintings and hundreds of copperplate etchings. At the time these works were dismissed by most as pornographic fantasies of an impotent old man or the slapdash works of an artist who was past his prime. Only later, after Picasso's death, when the rest of the art world had moved on from abstract expressionism, did the critical community come to see that Picasso had already discovered Neo-Expressionism and was, as so often before, ahead of his time.

Death[edit]

Pablo Picasso died on 8 April 1973 in Mougins, France, while he and his wife Jacqueline entertained friends for dinner. He was interred at the Chateau of Vauvenargues near Aix-en-Provence, a property he had acquired in 1958 and occupied with Jacqueline between 1959 and 1962. Jacqueline Roque prevented his children Claude and Paloma from attending the funeral.[51] Devastated and lonely after the death of Picasso, Jacqueline Roque killed herself by gunshot in 1986 when she was 59 years old.[52]

Political views[edit]

Aside from the several anti-war paintings that he created, Picasso remained personally neutral during World War I, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II, refusing to join the armed forces for any side or country. He had also remained aloof from the Catalan independence movement during his youth despite expressing general support and being friendly with activists within it. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1937, Picasso was already in his late fifties. He was even older at the onset of World War II, and could not be expected to take up arms in those conflicts. As a Spanish citizen living in France, Picasso was under no compulsion to fight against the invading Germans in either World War. In the Spanish Civil War, service for Spaniards living abroad was optional and would have involved a voluntary return to their country to join either side. While Picasso expressed anger and condemnation of Francisco Franco and fascists through his art, he did not take up arms against them. The Spanish Civil War provided the impetus for Picasso's first overtly political work, The Dream and Lie of Franco which was produced "specifically for propagandistic and fundraising purposes."[53] This surreal fusion of words and images was intended to be sold as a series of postcards to raise funds for the Spanish Republican cause.[53][54]

In 1944 Picasso joined the French Communist Party, attended an international peace conference in Poland, and in 1950 received the Stalin Peace Prize from the Soviet government,[55] But party criticism of a portrait of Stalin as insufficiently realistic cooled Picasso's interest in Soviet politics, though he remained a loyal member of the Communist Party until his death. In a 1945 interview with Jerome Seckler, Picasso stated: "I am a Communist and my painting is Communist painting. ... But if I were a shoemaker, Royalist or Communist or anything else, I would not necessarily hammer my shoes in a special way to show my politics."[56] His Communist militancy, common among continental intellectuals and artists at the time (although it was officially banned in Francoist Spain), has long been the subject of some controversy; a notable source or demonstration thereof was a quote commonly attributed to Salvador Dalí (with whom Picasso had a rather strained relationship[57]):

- Picasso es pintor, yo también; [...] Picasso es español, yo también; Picasso es comunista, yo tampoco.

- (Picasso is a painter, so am I; [...] Picasso is a Spaniard, so am I; Picasso is a communist, neither am I.)[58][59][60]

In the late 1940s his old friend the surrealist poet and Trotskyist[61] and anti-Stalinist André Breton was more blunt; refusing to shake hands with Picasso, he told him: "I don't approve of your joining the Communist Party nor with the stand you have taken concerning the purges of the intellectuals after the Liberation".[62]

In 1962, he received the Lenin Peace Prize.[63] Biographer and art critic John Berger felt his talents as an artist were "wasted" by the communists.[64]

According to Jean Cocteau's diaries, Picasso once said to him in reference to the communists: "I have joined a family, and like all families, it's full of shit".[65]

He was against the intervention of the United Nations and the United States[66] in the Korean War and he depicted it in Massacre in Korea.

Style and technique[edit]

Picasso was exceptionally prolific throughout his long lifetime. The total number of artworks he produced has been estimated at 50,000, comprising 1,885 paintings; 1,228 sculptures; 2,880 ceramics, roughly 12,000 drawings, many thousands of prints, and numerous tapestries and rugs.[67]

The medium in which Picasso made his most important contribution was painting.[68] In his paintings, Picasso used color as an expressive element, but relied on drawing rather than subtleties of color to create form and space.[68] He sometimes added sand to his paint to vary its texture. A nanoprobe of Picasso's The Red Armchair (1931) by physicists at Argonne National Laboratory in 2012 confirmed art historians' belief that Picasso used common house paint in many of his paintings.[69] Much of his painting was done at night by artificial light.

Picasso's early sculptures were carved from wood or modeled in wax or clay, but from 1909 to 1928 Picasso abandoned modeling and instead made sculptural constructions using diverse materials.[68] An example is Guitar (1912), a relief construction made of sheet metal and wire that Jane Fluegel terms a "three-dimensional planar counterpart of Cubist painting" that marks a "revolutionary departure from the traditional approaches, modeling and carving".[70]

From the beginning of his career, Picasso displayed an interest in subject matter of every kind,[71] and demonstrated a great stylistic versatility that enabled him to work in several styles at once. For example, his paintings of 1917 included the pointillist Woman with a Mantilla, the Cubist Figure in an Armchair, and the naturalistic Harlequin (all in the Museu Picasso, Barcelona). In 1919, he made a number of drawings from postcards and photographs that reflect his interest in the stylistic conventions and static character of posed photographs.[72] In 1921 he simultaneously painted several large neoclassical paintings and two versions of the Cubist composition Three Musicians (Museum of Modern Art, New York; Philadelphia Museum of Art).[38] In an interview published in 1923, Picasso said, "The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution, or as steps towards an unknown ideal of painting ... If the subjects I have wanted to express have suggested different ways of expression I have never hesitated to adopt them."[38]

Although his Cubist works approach abstraction, Picasso never relinquished the objects of the real world as subject matter. Prominent in his Cubist paintings are forms easily recognized as guitars, violins, and bottles.[73] When Picasso depicted complex narrative scenes it was usually in prints, drawings, and small-scale works; Guernica (1937) is one of his few large narrative paintings.[72]

Picasso painted mostly from imagination or memory. According to William Rubin, Picasso "could only make great art from subjects that truly involved him ... Unlike Matisse, Picasso had eschewed models virtually all his mature life, preferring to paint individuals whose lives had both impinged on, and had real significance for, his own."[74] The art critic Arthur Danto said Picasso's work constitutes a "vast pictorial autobiography" that provides some basis for the popular conception that "Picasso invented a new style each time he fell in love with a new woman".[74] The autobiographical nature of Picasso's art is reinforced by his habit of dating his works, often to the day. He explained: "I want to leave to posterity a documentation that will be as complete as possible. That's why I put a date on everything I do."[74]

Artistic legacy[edit]

At the time of Picasso's death many of his paintings were in his possession, as he had kept off the art market what he did not need to sell. In addition, Picasso had a considerable collection of the work of other famous artists, some his contemporaries, such as Henri Matisse, with whom he had exchanged works. Since Picasso left no will, his death duties (estate tax) to the French state were paid in the form of his works and others from his collection. These works form the core of the immense and representative collection of the Musée Picasso in Paris. In 2003, relatives of Picasso inaugurated a museum dedicated to him in his birthplace, Málaga, Spain, the Museo Picasso Málaga.

The Museu Picasso in Barcelona features many of his early works, created while he was living in Spain, including many rarely seen works which reveal his firm grounding in classical techniques. The museum also holds many precise and detailed figure studies done in his youth under his father's tutelage, as well as the extensive collection of Jaime Sabartés, his close friend and personal secretary.

Several paintings by Picasso rank among the most expensive paintings in the world. Garçon à la pipe sold for US$104 million at Sotheby's on 4 May 2004, establishing a new price record. Dora Maar au Chat sold for US$95.2 million at Sotheby's on 3 May 2006.[75] On 4 May 2010, Nude, Green Leaves and Bust was sold at Christie's for $106.5 million. The 1932 work, which depicts Picasso's mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter reclining and as a bust, was in the personal collection of Los Angeles philanthropist Frances Lasker Brody, who died in November 2009.[76] On 11 May 2015 his painting Women of Algiers set the record for the highest price ever paid for a painting when it sold for US$179.3 million at Christie's in New York.[77]

As of 2004, Picasso remained the top-ranked artist (based on sales of his works at auctions) according to the Art Market Trends report.[78] More of his paintings have been stolen than any other artist's;[79] the Art Loss Register has 550 of his works listed as missing.[80]

The Picasso Administration functions as his official Estate. The US copyright representative for the Picasso Administration is the Artists Rights Society.[81]

In the 1996 movie Surviving Picasso, Picasso is portrayed by actor Anthony Hopkins.[82] Picasso is also a character in Steve Martin's 1993 play, Picasso at the Lapin Agile.

Recent major exhibitions[edit]

Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris, an exhibition of 150 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and photographs from the Musée National Picasso in Paris. The exhibit touring schedule includes:

- 8 October 2010 – 17 January 2011, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, US.

- 19 February 2011 – 15 May 2011, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, US.

- 11 June 2011 – 9 October 2011, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, California, US.[83]

- 12 November 2011 – 25 March 2012, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney.[84]

- 28 April 2012 – 26 August 2012, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

-

Postage stamp, USSR, 1973. Picasso has been honoured on stamps worldwide.

-

Musée Picasso, Paris (Hotel Salé, 1659)

-

Art Museum Pablo Picasso Münster Arkaden

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Pierre Daix, Georges Boudaille, Joan Rosselet, Picasso, 1900-1906: catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint, Editions Ides et Calendes, 1988

- ^ "Picasso". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "The Guitar, MoMA". Moma.org. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ "Sculpture, Tate". Tate.org.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Green, Christopher (2003), Art in France: 1900–1940, New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, p. 77, ISBN 0300099088, retrieved 10 February 2013

- ^ Searle, Adrian (7 May 2002). "A momentous, tremendous exhibition". Guardian. UK. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Trachtman, Paul (February 2003). "Matisse & Picasso". Smithsonian. Smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ "Duchamp's urinal tops art survey". news.bbc.co.uk. 1 December 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ The name on his baptismal certificate differs slightly from the name on his birth record. On line Picasso Project

- ^ Hamilton, George H. (1976). "Picasso, Pablo Ruiz Y". In William D. Halsey (ed.). Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. 19. New York: Macmillan Educational Corporation. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Neil Cox (2010). The Picasso Book. Tate Publishing. p. 124. ISBN 9781854378439.

Unlike Matisse's chapel, the ruined Vallauris building had long since ceased to fulfill a religious function, so the atheist Picasso no doubt delighted in reinventing its use for the secular Communist cause of 'Peace'.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Wertenbaker 1967, 9.

- ^ Wertenbaker 1967, 11.

- ^ a b "Picasso: Creator and Destroyer – 88.06". Theatlantic.com. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ a b Wertenbaker 1967, 13.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, p.6.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, p. 14.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, p.37.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, pp. 87–108.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, p. 125.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, p.127.

- ^ Wattenmaker, Distel, et al. 1993, p. 304.

- ^ "BBC News - Hidden painting found under Picasso's The Blue Room". Bbc.com. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ The Frugal Repast, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Wattenmaker, Distel, et al. 1993, p. 194.

- ^ "Portrait of Gertrude Stein". Metropolitan Museum. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Special Exhibit Examines Dynamic Relationship Between the Art of Pablo Picasso and Writing" (PDF). Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ James R. Mellow. Charmed Circle. Gertrude Stein and Company.

- ^ "Cubism and its Legacy". Tate Liverpool. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Richard Lacayo (7 April 2009). "Art's Great Whodunit: The Mona Lisa Theft of 1911". TIME. Time Inc. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ a b c John Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-1932, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Dec 24, 2008, pp. 77-78, ISBN 030749649X

- ^ Letter from Juan Gris to Maurice Raynal, 23 May 1917, Kahnweiler-Gris 1956, 18

- ^ Paul Morand, 1996, 19 May 1917, p. 143-4

- ^ Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 13-47

- ^ Harrison, Charles; Frascina, Francis; Perry, Gillian (1993). Primitivism, Cubism, Abstraction. Google Books. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Melissa McQuillan, ''Primitivism and Cubism, 1906–15, War Years'', From Grove Art Online, MoMA". Moma.org. 14 December 1915. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Paul (Paolo) Picasso is born". Xtimeline.com. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Cowling & Mundy 1990, p. 201.

- ^ a b c "Melissa McQuillan, ''Pablo Picasso, Interactions with Surrealism, 1925–35'', from Grove Art Online, 2009 Oxford University Press, MoMA". Moma.org. 12 January 1931. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Richard Dorment (8 May 2012). "Picasso, The Vollard Suite, British Museum, review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ The MoMA retrospective of 1939–40 — see Michael C. FitzGerald, Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), pp. 243–262.

- ^ "Guernica Introduction". Pbs.org. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ The Spanish Wars of Goya and Picasso, Costa Tropical News. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Reagan, Geoffrey (1992). Military Anecdotes. Guinness Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 0-85112-519-0

- ^ Kendall, L. R., Pablo Picasso (1881–1973): The Charnel House in Pieces... Occasional and Various April 2010

- ^ Artnet, Fred Stern, Picasso and the War Year Retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ Lorentz, Stanisław (2002). Sarah Wilson (ed.). Paris: capital of the arts, 1900–1968. Royal Academy of Arts. p. 429. ISBN 09-00946-98-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Rothenberg, Jerome. Pablo Picasso, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz & other poems. Exact Exchange Books, Cambridge, MA, 2004, vii–xviii

- ^ Picasso the Playwright, Picasso's Little Recognised Contribution to the Performing Arts - with Images Retrieved April 2015

- ^ Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake, Life with Picasso, Random House. May 1989. ISBN 0-385-26186-1; first published in November 1964.

- ^ Zabel, William D (1996).The Rich Die Richer and You Can too. John Wiley and Sons, p.11. ISBN 0-471-15532-2

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (28 April 1996). "Picasso's Family Album,". New York Times. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Picasso's commitment to the cause". PBS.

- ^ National Gallery of Victoria (2006). "An Introduction to Guernica". Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ Picasso’s Party Line, ARTnews Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ Ashton, Dore and Pablo Picasso (1988). Picasso on Art: A Selection of Views. Da Capo Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-306-80330-5.

- ^ "Failed attempts at correspondence between Dalí and Picasso". Larepublica.com.pe. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Study on Salvador Dalí". Monografias.com. 7 May 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Article on Dalí in ',El Mundo',". Elmundo.es. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Dannatt, Adrian (7 June 2010), Picasso: Peace and Freedom. Tate Liverpool, 21 May – 30 August 2010, Studio International, retrieved 10 February 2013

- ^ Rivera, Breton and Trotsky Retrieved 9 August 2010

- ^ Huffington, Arianna S. (1988). Picasso: Creator and Destroyer. Simon and Schuster. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-7861-0642-4.

- ^ "Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881–1973) | Picasso gets Stalin Peace Prize | Event view". Xtimeline.com. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Berger, John (1965). The Success and Failure of Picasso. Penguin Books, Ltd. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-679-73725-4.

- ^ Charlotte Higgins (28 May 2010). "Picasso nearly risked his reputation for Franco exhibition". The Guardian. UK: Guardian News and Media.

- ^ Picasso A Retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, edited by William Rubin, copyright MoMA 1980, p.383

- ^ On-line Picasso Project, citing Selfridge, John, 1994.

- ^ a b c McQuillan, Melissa. "Picasso, Pablo." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed February 1, 2014

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (8 February 2013). "Picasso's Genius Revealed: He Used Common House Paint", Live Science. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Rubin 1980, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, p. 164.

- ^ a b Cowling & Mundy 1990, p. 208.

- ^ Cirlot 1972, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c Danto, Arthur (August 26/September 2, 1996). "Picasso and the Portrait". The Nation 263 (6): 31–35.

- ^ "Picasso portrait sells for $95.2 million". Retrieved 4 May 2006.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (9 March 2010). "Christie's Wins Bid to Auction $150 Million Brody Collection". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Picasso painting smashes art auction record in $179.4m sale, International Business Times, May 12, 2015

- ^ "2004 Art Market Trends report" (PDF). Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ S. Goodenough, 1500 Fascinating Facts, Treasure Press, London, 1987, p 241.

- ^ Revealed: The extraordinary security blunders behind Paris art gallery heist The Daily Mail

- ^ "Most frequently requested artists list of the Artists Rights Society". Arsny.com. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ [1]IMDB

- ^ "Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris". deYoung Museum. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales". Artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

References[edit]

- Becht-Jördens, Gereon; Wehmeier, Peter M. (2003). Picasso und die christliche Ikonographie: Mutterbeziehung und künstlerische Position. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-496-01272-6.

- Berger, John (1989). The success and failure of Picasso. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-679-72272-4.

- Cirlot, Juan Eduardo (1972). Picasso, birth of a genius. New York and Washington: Praeger.

- Cowling, Elizabeth; Mundy, Jennifer (1990). On classic ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism, 1910–1930. London: Tate Gallery. ISBN 978-1-85437-043-3.

- Daix, Pierre (1994). Picasso: life and art. Icon Editions. ISBN 978-0-06-430201-2.

- FitzGerald, Michael C. (1996). Making modernism: Picasso and the creation of the market for twentieth-century art. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20653-3.

- Granell, Eugenio Fernández (1981). Picasso's Guernica: the end of a Spanish era. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press. ISBN 978-0-8357-1206-4.

- Krauss, Rosalind E. (1999). The Picasso papers. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-61142-8.

- Mallén, Enrique (2003). The visual grammar of Pablo Picasso. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-5692-8.

- Mallén, Enrique (2005). La sintaxis de la carne: Pablo Picasso y Marie-Thérèse Walter. Santiago de Chile: Red Internacional del Libro. ISBN 978-956-284-455-0.

- Mallén, Enrique (2009). A Concordance of Pablo Picasso's Spanish Writings. New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-4713-4.

- Mallén, Enrique (2010). A Concordance of Pablo Picasso's French Writings. New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-1325-2. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- Nill, Raymond M (1987). A Visual Guide to Pablo Picasso's Works. New York: B&H Publishers.

- Picasso, Olivier Widmaier (2004). Picasso: the real family story. Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-3149-2.

- Rubin, William (1981). Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective. Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0-316-70703-9.

- Wattenmaker, Richard J. (1993). Great French paintings from the Barnes Foundation: Impressionist, Post-impressionist, and Early Modern. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-40963-2.

- Wertenbaker, Lael Tucker (1967). The world of Picasso (1881– ). Time-Life Books.

External links[edit]

- Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Pablo Picasso. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California

- Picasso's Little Recognised Contribution to the Performing Arts - with images

- Picasso's works at the Guggenheim Museum

- Works by or about Amimouni in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Guggenheim Museum Biography

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

- Musée National Picasso (Paris, France)

- Pablo Picasso in the National Portal of the "Museums in Israel"

- Museo Picasso Málaga (Málaga, Spain)

- Museu Picasso (Barcelona, Spain)

- Amimouni at the Museum of Modern Art

- National Gallery of Art

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) (Los Angeles, California)

Category:1881 births Category:1973 deaths Category:People from Málaga Category:Spanish expatriates in France Category:19th-century Spanish painters Category:20th-century Spanish painters Category:20th-century sculptors Category:Ballet designers Category:Cubist artists Category:French Communist Party members Category:Lenin Peace Prize recipients Category:Modern painters Category:School of Paris Category:Spanish atheists Category:Spanish communists Category:Spanish muralists Category:Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (Republican faction) Category:Spanish potters Category:Spanish sculptors Category:Child artists Category:Directors of the Museo del Prado Category:Painters of the Return to Order

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_100_x_80_cm%2C_Staatliche_Museen_zu_Berlin%2C_Neue_Nationalgalerie.jpg/141px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1909%2C_Femme_assise_(Sitzende_Frau)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_100_x_80_cm%2C_Staatliche_Museen_zu_Berlin%2C_Neue_Nationalgalerie.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_92.1_x_73_cm%2C_Tate_Modern%2C_London.jpg/138px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1909-10%2C_Figure_dans_un_Fauteuil_(Seated_Nude%2C_Femme_nue_assise)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_92.1_x_73_cm%2C_Tate_Modern%2C_London.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_73_x_60_cm%2C_Gemeentemuseum%2C_The_Hague._Exhibited_at_the_Armory_Show%2C_New_York%2C_Chicago%2C_Boston_1913.jpg/148px-thumbnail.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_100.3_x_73.6_cm%2C_Museum_of_Modern_Art_New_York..jpg/130px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1910%2C_Girl_with_a_Mandolin_(Fanny_Tellier)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_100.3_x_73.6_cm%2C_Museum_of_Modern_Art_New_York..jpg)

%2C_Céret%2C_oil_on_linen%2C_131.2_×_89.5_cm%2C_The_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Foundation%2C_Peggy_Guggenheim_Collection%2C_Venice.jpg/120px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1911%2C_The_Poet_(Le_poète)%2C_Céret%2C_oil_on_linen%2C_131.2_×_89.5_cm%2C_The_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Foundation%2C_Peggy_Guggenheim_Collection%2C_Venice.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_Kröller-Müller_Museum%2C_Otterlo%2C_Netherlands.jpg/139px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1911-12%2C_Violon_(Violin)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_Kröller-Müller_Museum%2C_Otterlo%2C_Netherlands.jpg)

%2C_cut_and_pasted_colored_paper%2C_gouache_and_charcoal_on_paperboard%2C_43.5_x_33_cm%2C_Scottish_National_Gallery_of_Modern_Art%2C_Edinburgh.jpg/137px-thumbnail.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_108_x_89.5_cm%2C_Museum_of_Modern_Art%2C_New_York.jpg/148px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1913-14%2C_L%27Homme_aux_cartes_(Card_Player)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_108_x_89.5_cm%2C_Museum_of_Modern_Art%2C_New_York.jpg)

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_63.5_x_78.7_cm_(25_x_31_in)%2C_Columbus_Museum_of_Art%2C_Ohio.jpg/170px-thumbnail.jpg)

_oil_on_canvas%2C_46_x_54.6_cm%2C_Detroit_Institute_of_Arts%2C_Michigan.jpg/170px-Pablo_Picasso%2C_1916%2C_L%27anis_del_mono_(Bottle_of_Anis_del_Mono)_oil_on_canvas%2C_46_x_54.6_cm%2C_Detroit_Institute_of_Arts%2C_Michigan.jpg)