Germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade humans, other animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers to not just a bacterium but to any type of microorganism, such as protists or fungi, or even non-living pathogens that can cause disease, such as viruses, prions, or viroids.[1] Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious diseases. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-carrying agents that can pass from one individual to another, both in humans and animals. Infectious diseases are caused by biological agents such as pathogenic microorganisms (viruses, bacteria, and fungi) as well as parasites.

Basic forms of germ theory were proposed by Girolamo Fracastoro in 1546, and expanded upon by Marcus von Plenciz in 1762. However, such views were held in disdain in Europe, where Galen's miasma theory remained dominant among scientists and doctors.

By the early 19th century, smallpox vaccination was commonplace in Europe, though doctors were unaware of how it worked or how to extend the principle to other diseases. A transitional period began in the late 1850s with the work of Louis Pasteur. This work was later extended by Robert Koch in the 1880s. By the end of that decade, the miasma theory was struggling to compete with the germ theory of disease. Viruses were initially discovered in the 1890s. Eventually, a "golden era" of bacteriology ensued, during which the germ theory quickly led to the identification of the actual organisms that cause many diseases.[2]

Miasma theory[edit]

The miasma theory was the predominant theory of disease transmission before the germ theory took hold towards the end of the 19th century; it is no longer accepted as a correct explanation for disease by the scientific community. It held that diseases such as cholera, chlamydia infection, or the Black Death were caused by a miasma (μίασμα, Ancient Greek: "pollution"), a noxious form of "bad air" emanating from rotting organic matter.[3] Miasma was considered to be a poisonous vapor or mist filled with particles from decomposed matter (miasmata) that was identifiable by its foul smell. The theory posited that diseases were the product of environmental factors such as contaminated water, foul air, and poor hygienic conditions. Such infections, according to the theory, were not passed between individuals but would affect those within a locale that gave rise to such vapors.[4]

Development[edit]

Ancient India[edit]

Ancient Indian Rishis such as Kanva described tiny creatures called Krimi and their harmful effects in the Atharvaveda.[5]

Greece and Rome[edit]

In Antiquity, the Greek historian Thucydides (c. 460 – c. 400 BC) was the first person to write, in his account of the plague of Athens, that diseases could spread from an infected person to others.[6][7]

One theory of the spread of contagious diseases that were not spread by direct contact was that they were spread by spore-like "seeds" (Latin: semina) that were present in and dispersible through the air. In his poem, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things, c. 56 BC), the Roman poet Lucretius (c. 99 BC – c. 55 BC) stated that the world contained various "seeds", some of which could sicken a person if they were inhaled or ingested.[8][9]

The Roman statesman Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) wrote, in his Rerum rusticarum libri III (Three Books on Agriculture, 36 BC): "Precautions must also be taken in the neighborhood of swamps... because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases."[10]

The Greek physician Galen (AD 129 – c. 200/216) speculated in his On Initial Causes (c. 175 AD that some patients might have "seeds of fever".[8]: 4 In his On the Different Types of Fever (c. 175 AD), Galen speculated that plagues were spread by "certain seeds of plague", which were present in the air.[8]: 6 And in his Epidemics (c. 176–178 AD), Galen explained that patients might relapse during recovery from fever because some "seed of the disease" lurked in their bodies, which would cause a recurrence of the disease if the patients did not follow a physician's therapeutic regimen.[8]: 7

The Middle Ages[edit]

A basic form of contagion theory dates back to medicine in the medieval Islamic world, where it was proposed by Persian physician Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe) in The Canon of Medicine (1025), which later became the most authoritative medical textbook in Europe up until the 16th century. In Book IV of the El-Kanun, Ibn Sina discussed epidemics, outlining the classical miasma theory and attempting to blend it with his own early contagion theory. He mentioned that people can transmit disease to others by breath, noted contagion with tuberculosis, and discussed the transmission of disease through water and dirt.[11]

The concept of invisible contagion was later discussed by several Islamic scholars in the Ayyubid Sultanate who referred to them as najasat ("impure substances"). The fiqh scholar Ibn al-Haj al-Abdari (c. 1250–1336), while discussing Islamic diet and hygiene, gave warnings about how contagion can contaminate water, food, and garments, and could spread through the water supply, and may have implied contagion to be unseen particles.[12]

During the early Middle Ages, Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) mentioned "plague-bearing seeds" (pestifera semina) in his On the Nature of Things (c. AD 613).[8]: 20 Later in 1345, Tommaso del Garbo (c. 1305–1370) of Bologna, Italy mentioned Galen's "seeds of plague" in his work Commentaria non-parum utilia in libros Galeni (Helpful commentaries on the books of Galen).[8]: 214

In 1546, Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro published De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis (On Contagion and Contagious Diseases), a set of three books covering the nature of contagious diseases, categorization of major pathogens, and theories on preventing and treating these conditions. Fracastoro blamed "seeds of disease" that propagate through direct contact with an infected host, indirect contact with fomites, or through particles in the air.[13]

The Early Modern Period[edit]

In 1668, Italian physician Francesco Redi published experimental evidence rejecting spontaneous generation, the theory that living creatures arise from nonliving matter. He observed that maggots only arose from rotting meat that was uncovered. When meat was left in jars covered by gauze, the maggots would instead appear on the gauze's surface, later understood as rotting meat's smell passing through the mesh to attract flies that laid eggs.[14][15]

Microorganisms are said to have been first directly observed in the 1670s by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, an early pioneer in microbiology, considered "the Father of Microbiology". Leeuwenhoek is said to be the first to see and describe bacteria (1674), yeast cells, the teeming life in a drop of water (such as algae), and the circulation of blood corpuscles in capillaries. The word "bacteria" didn't exist yet, so he called these microscopic living organisms "animalcules", meaning "little animals". Those "very little animalcules" he was able to isolate from different sources, such as rainwater, pond and well water, and the human mouth and intestine. Yet German Jesuit priest and scholar Athanasius Kircher may have observed such microorganisms prior to this. One of his books written in 1646 contains a chapter in Latin, which reads in translation "Concerning the wonderful structure of things in nature, investigated by Microscope", stating "who would believe that vinegar and milk abound with an innumerable multitude of worms." Kircher defined the invisible organisms found in decaying bodies, meat, milk, and secretions as "worms." His studies with the microscope led him to the belief, which he was possibly the first to hold, that disease and putrefaction (decay) were caused by the presence of invisible living bodies. In 1646, Kircher (or "Kirchner", as it is often spelled), wrote that "a number of things might be discovered in the blood of fever patients." When Rome was struck by the bubonic plague in 1656, Kircher investigated the blood of plague victims under the microscope. He noted the presence of "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganisms. He was the first to attribute infectious disease to a microscopic pathogen, inventing the germ theory of disease, which he outlined in his Scrutinium Physico-Medicum (Rome 1658).[16] Kircher's conclusion that disease was caused by microorganisms was correct, although it is likely that what he saw under the microscope were in fact red or white blood cells and not the plague agent itself. Kircher also proposed hygienic measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine, burning clothes worn by the infected, and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germs. It was Kircher who first proposed that living beings enter and exist in the blood.

In 1700, physician Nicolas Andry argued that microorganisms he called "worms" were responsible for smallpox and other diseases.[17]

In 1720, Richard Bradley theorised that the plague and "all pestilential distempers" were caused by "poisonous insects", living creatures viewable only with the help of microscopes.[18]

In 1762, the Austrian physician Marcus Antonius von Plenciz (1705–1786) published a book titled Opera medico-physica. It outlined a theory of contagion stating that specific animalcules in the soil and the air were responsible for causing specific diseases. Von Plenciz noted the distinction between diseases which are both epidemic and contagious (like measles and dysentery), and diseases which are contagious but not epidemic (like rabies and leprosy).[19] The book cites Anton van Leeuwenhoek to show how ubiquitous such animalcules are and was unique for describing the presence of germs in ulcerating wounds. Ultimately, the theory espoused by von Plenciz was not accepted by the scientific community.

19th and 20th centuries[edit]

It has been suggested that Germ theory's key 19th century figures be merged into this section. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2023. |

Agostino Bassi, Italy[edit]

During the early 19th century, driven by economic concerns over collapsing silk production, Italian entomologist Agostino Bassi researched a silkworm disease known as "muscardine" (type of white bonbon) in French and "calcinaccio" (rubble) or "mal del segno" (bad sign) in Italian, due to the disease causing white fungal spots along the caterpillar. From 1835 to 1836, Bassi published his findings that fungal spores transmitted the disease between individuals. In recommending the rapid removal of diseased caterpillars and disinfection of their surfaces, Bassi outlined methods used in modern preventative healthcare.[20] Italian naturalist Giuseppe Gabriel Balsamo-Crivelli named the causative fungal species after Bassi, currently classified as Beauveria bassiana.[21]

Louis-Daniel Beauperthuy, France[edit]

In 1838 French specialist in tropical medicine Louis-Daniel Beauperthuy pioneered using microscopy in relation to diseases and independently developed a theory that all infectious diseases were due to parasitic infection with "animalcules" (microorganisms). With the help of his friend M. Adele de Rosseville, he presented his theory in a formal presentation before the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. By 1853, he was convinced that malaria and yellow fever were spread by mosquitos. He even identified the particular group of mosquitos that transmit yellow fever as the "domestic species" of "striped-legged mosquito", which can be recognised as Aedes aegypti, the actual vector. He published his theory in 1854 in the Gaceta Oficial de Cumana ("Official Gazette of Cumana"). His reports were assessed by an official commission, which discarded his mosquito theory.[22]

Ignaz Semmelweis, Austria[edit]

Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian obstetrician working at the Vienna General Hospital (Allgemeines Krankenhaus) in 1847, noticed the dramatically high maternal mortality from puerperal fever following births assisted by doctors and medical students. However, those attended by midwives were relatively safe. Investigating further, Semmelweis made the connection between puerperal fever and examinations of delivering women by doctors, and further realized that these physicians had usually come directly from autopsies. Asserting that puerperal fever was a contagious disease and that matter from autopsies were implicated in its development, Semmelweis made doctors wash their hands with chlorinated lime water before examining pregnant women. He then documented a sudden reduction in the mortality rate from 18% to 2.2% over a period of a year. Despite this evidence, he and his theories were rejected by most of the contemporary medical establishment.[23]

Gideon Mantell, UK[edit]

Gideon Mantell, the Sussex doctor more famous for discovering dinosaur fossils, spent time with his microscope, and speculated in his Thoughts on Animalcules (1850) that perhaps "many of the most serious maladies which afflict humanity, are produced by peculiar states of invisible animalcular life".[24]

John Snow, UK[edit]

British physician John Snow is credited as a founder of modern epidemiology for studying the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak.[25] Snow criticized the Italian anatomist Giovanni Maria Lancisi for his early 18th century writings that claimed swamp miasma spread malaria, rebutting that bad air from decomposing organisms was not present in all cases. In his 1849 pamphlet On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, Snow proposed that cholera spread through the fecal–oral route, replicating in human lower intestines.[26]

In the book's second edition, published in 1855, Snow theorized that cholera was caused by cells smaller than human epithelial cells, leading to Robert Koch's 1884 confirmation of the bacterial species Vibrio cholerae as the causative agent. In recognizing a biological origin, Snow recommended boiling and filtering water, setting the precedent for modern boil-water advisory directives.[26]

Through a statistical analysis tying cholera cases to specific water pumps associated with the Southwark and Vauxhall Waterworks Company, which supplied sewage-polluted water from the River Thames, Snow showed that areas supplied by this company experienced fourteen times as many deaths as residents using Lambeth Waterworks Company pumps that obtained water from the upriver, cleaner Seething Wells. While Snow received praise for convincing the Board of Guardians of St James's Parish to remove the handles of contaminated pumps, he noted that the outbreak's cases were already declining as scared residents fled the region.[26]

Louis Pasteur, France[edit]

During the mid-19th century, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur showcased that treating the female genital tract with boric acid killed the microorganisms causing postpartum infections while avoiding damage to mucous membranes.[27]

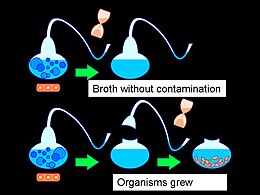

Building on Redi's work, Pasteur disproved spontaneous generation by constructing swan neck flasks containing nutrient agar. Since the flask contents were only fermented when in direct contact with the external environment's air by removing the curved tubing, Pasteur demonstrated that bacteria must travel between sites of infection to colonize environments.[28]

Similar to Bassi, Pasteur extended his research on germ theory by studying pébrine, a disease that causes brown spots on silkworms.[21] While Swiss botanist Carl Nägeli discovered the fungal species Nosema bombycis in 1857, Pasteur applied the findings to recommend improved ventilation and screening of silkworm eggs, an early form of disease surveillance.[28]

Robert Koch, Germany[edit]

In 1884, German bacteriologist Robert Koch published four criteria for establishing causality between specific microorganisms and diseases, now known as Koch's postulates:[29]

- The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms with the disease, but should not be found in healthy organisms.

- The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

- The cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

- The microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

During his lifetime, Koch recognized that the postulates were not universally applicable, such as asymptomatic carriers of cholera violating the first postulate. For this same reason, the third postulate specifies "should", rather than "must", because not all host organisms exposed to an infectious agent will acquire the infection, potentially due to differences in prior exposure to the pathogen.[30][31] Furthermore, viruses cannot be grown in pure cultures because they are obligate intracellular parasites, making it impossible to fulfill the second postulate.[32][33] Similarly, pathogenic misfolded proteins, known as prions, only spread by transmitting their structure to other proteins, rather than self-replicating.[34]

While Koch's postulates retain historical importance for emphasizing that correlation does not imply causation, many pathogens are accepted as causative agents of specific diseases without fulfilling all of the criteria.[35] In 1988, American microbiologist Stanley Falkow published a molecular version of Koch's postulates to establish correlation between microbial genes and virulence factors.[36]

Joseph Lister, UK[edit]

After reading Pasteur's papers on bacterial fermentation, British surgeon Joseph Lister recognized that compound fractures, involving bones breaking through the skin, were more likely to become infected due to exposure to environmental microorganisms. He recognized that carbolic acid could be applied to the site of injury as an effective antiseptic.[37]

See also[edit]

- Alexander Fleming

- Cell theory

- Epidemiology

- Germ theory denialism

- History of emerging infectious diseases

- Robert Hooke

- Rudolf Virchow

- Zymotic disease

References[edit]

- ^ "Definition of Germ in English from the Oxford dictionary". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Susser, Mervyn; Stein, Zena (August 2009). Chapter 10: Germ Theory, Infection, and Bacteriology. Oxford University Press. pp. 107–122. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195300666.003.0010. ISBN 9780199863754.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Last JM, ed. (2007), "miasma theory", A Dictionary of Public Health, Westminster College, Pennsylvania: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195160901

- ^ Tsoucalas G, Spengos K, Panayiotakopoulos G, Papaioannou T, Karamanou M (15 February 2018). "Epilepsy, Theories and Treatment Inside Corpus Hippocraticum". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 23 (42): 6369–6372. doi:10.2174/1381612823666171024153144. PMID 29076418.

- ^ Kuhad, Urvashi; Goel, Gunjan; Maurya, Pawan K.; Kuhad, Ramesh C. (19 October 2020). "Sukshmjeevanu in Vedas: The Forgotten Past of Microbiology in Indian Vedic Knowledge". Indian J Microbiol. 61 (1): 108–110. doi:10.1007/s12088-020-00911-5. PMC 7810802. PMID 33505101.

- ^ Singer, Charles and Dorothea (1917) "The scientific position of Girolamo Fracastoro [1478?–1553] with especial reference to the source, character and influence of his theory of infection," Annals of Medical History, 1 : 1–34; see p. 14. Archived 16 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thucydides with Richard Crawley, trans., History of the Peloponnesian War (London, England: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910), Book III, § 51, pp. 131–32. From pp. 131–32: " … there was the awful spectacle of men dying like sheep, through having caught the infection in nursing each other. This caused the greatest mortality. On the one hand, if they were afraid to visit each other, they perished from neglect; indeed many houses were emptied of their inmates for want of a nurse: on the other, if they ventured to do so, death was the consequence."

- ^ a b c d e f Nutton V (January 1983). "The seeds of disease: an explanation of contagion and infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance". Medical History. 27 (1): 1–34. doi:10.1017/s0025727300042241. PMC 1139262. PMID 6339840.

- ^ Lucretius with Rev. John S. Watson, trans., On the Nature of Things (London, England: Henry G. Bohn, 1851), Book VI, lines 1093–1130, pp. 291–92; see especially p. 292. From p. 292: "This new malady and pest, therefore, either suddenly falls into the water, or penetrates into the very corn, or into other food of men and cattle. Or even, as may be the case, the infection remains suspended in the air itself; and when, as we breathe, we inhale the air mingled with it, we must necessarily absorb those seeds of disease into our body."

- ^ Varro MT, Storr-Best L (1912). "XII". Varro on Farming. Vol. Book 1. London, England: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd. p. 9.

- ^ Byrne JP (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Death. ABC-CLIO. p. 29. ISBN 9781598842531.

- ^ Reid MH (2013). Law and Piety in Medieval Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 106, 114, 189–190. ISBN 9781107067110.

- ^ Morgan, Ewan (22 January 2021). "The Physician Who Presaged the Germ Theory of Disease Nearly 500 Years Ago". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Redi, Francesco (1668). Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degl' Insetti [Experiments on the Generation of Insects] (in Italian). Florence, Italy. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.149072. LCCN 18018365. OCLC 9363778. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Parke, Emily C. (1 March 2014). "Flies from meat and wasps from trees: Reevaluating Francesco Redi's spontaneous generation experiments". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 45: 34–42. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.12.005. ISSN 1369-8486. PMID 24509515. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "The Life and Work of Athanaseus Kircher, S.J." mjt.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ "The History of the Germ Theory". The British Medical Journal. 1 (1415): 312. 1888.

- ^ Santer M (2009). "Richard Bradley: a unified, living agent theory of the cause of infectious diseases of plants, animals, and humans in the first decades of the 18th century". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 52 (4): 566–78. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0124. PMID 19855125. S2CID 22544615.

- ^ Winslow CE (1967). Conquest of Epidemic Disease: A Chapter in the History of Ideas. Hafner Publishing Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0028548807.

- ^ Bassi, Agostino (1836). Del Mal del Segno, Calcinaccio o Moscardino : Malattia che Affligge i Bachi da Seta [Bad Sign, Rubble, or Muscardine: Disease that Afflicts Silkworms] (in Italian). Lodi, Lombardy. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.152962. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b Lovett, Brian (6 December 2019). "Sick or Silk: How Silkworms Spun the Germ Theory of Disease". American Society for Microbiology. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Agramonte, A (2001). "The inside history of a great medical discovery. 1915". Military Medicine. 166 (9 Suppl): 68–78. doi:10.1093/milmed/166.suppl_1.68. PMID 11569397.

- ^ Carter KC (January 1985). "Ignaz Semmelweis, Carl Mayrhofer, and the rise of germ theory". Medical History. 29 (1): 33–53. doi:10.1017/S0025727300043738. PMC 1139480. PMID 3883083.

- ^ From p. 90 of "The invisible world revealed by the microscope or, thoughts on animalcules.", second edition, 1850 (May have appeared in first edition, too. (Revise date in article to 1846, if so.))

- ^ Snowise, Neil G. (7 May 2021). "Memorials to John Snow - Pioneer in Anaesthesia and Epidemiology". Journal of Medical Biography. SAGE Publishing. 31 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1177/09677720211013807. ISSN 1758-1087. PMC 9925902. PMID 33960862. S2CID 233985110.

- ^ a b c Snow, John (1855). On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (2nd ed.). London: John Churchill. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Pasteur, Louis (3 May 1880). Translated by H.C. Ernst. "Extension Of The Germ Theory To The Etiology Of Certain Common Disease". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. French Academy of Sciences. 90: 1033–44. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023 – via Fordham University Modern History Sourcebook.

- ^ a b "The Middle Years 1862-1877". Pasteur Institute. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Walker L, Levine H, Jucker M (July 2006). "Koch's postulates and infectious proteins". Acta Neuropathologica. 112 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0072-x. PMC 8544537. PMID 16703338. S2CID 22210933.

- ^ Koch R (1884). "Die Aetiologie der Tuberkulose". Mittheilungen aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte. Vol. 2. pp. 1–88.

- ^ Koch R (1893). "Über den augenblicklichen Stand der bakteriologischen Choleradiagnose". Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten (in German). 14: 319–33. doi:10.1007/BF02284324. S2CID 9388121. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Brock TD (1999). Robert Koch: a life in medicine and bacteriology. Washington DC: American Society of Microbiology Press. ISBN 1-55581-143-4.

- ^ Evans AS (May 1976). "Causation and disease: the Henle-Koch postulates revisited". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 49 (2): 175–195. PMC 2595276. PMID 782050.

- ^ Inglis TJ (November 2007). "Principia aetiologica: taking causality beyond Koch's postulates". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 56 (Pt 11): 1419–1422. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.47179-0. PMID 17965339.

- ^ Jacomo V, Kelly PJ, Raoult D (January 2002). "Natural history of Bartonella infections (an exception to Koch's postulate)". Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 9 (1): 8–18. doi:10.1128/CDLI.9.1.8-18.2002. PMC 119901. PMID 11777823.

- ^ Falkow S (1988). "Molecular Koch's postulates applied to microbial pathogenicity" (PDF). Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 10 (Suppl 2): S274–S276. doi:10.1093/cid/10.Supplement_2.S274. PMID 3055197. S2CID 13602080. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2019.

- ^ Pitt, Dennis; Aubin, Jean-Michel (1 October 2012). "Joseph Lister: Father of Modern Surgery". Canadian Journal of Surgery. 55 (5): E8–E9. doi:10.1503/cjs.007112. PMC 3468637. PMID 22992425. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

External links[edit]

- Stephen T. Abedon Germ Theory of Disease Supplemental Lecture (98/03/28 update)

- William C. Campbell The Germ Theory Timeline

- Science's war on infectious diseases